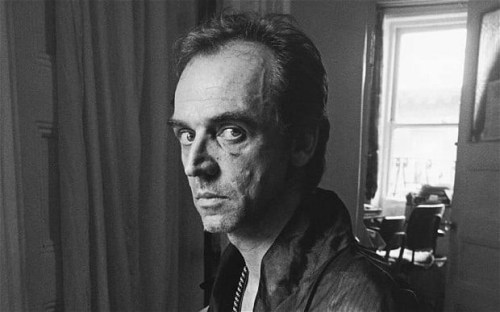

Rene Ricard, who has died of cancer aged 67, was a cultural provocateur in Andy Warhol’s circle of oddballs, transsexuals and aspiring “superstars”.

Art critic, actor, poet and painter, Ricard was a Renaissance man for the cocaine age. However, he accepted that, by conventional terms, he had never worked a day in his life. “If I did,” he said in the 1970s, “it would probably ruin my career, which at the moment is something of a cross between a butterfly and a lapdog.”

Ricard’s contemplative, literary-minded nature was at odds with the more chaotic aspects of Warhol’s studio entourage at The Factory. To his famous mentor, he was “the George Sanders of the Lower East Side”. Not that Ricard was able to emulate the laconic Hollywood star: in Warhol’s 1965 film Kitchen, Ricard was seen washing dishes to the hum of a refrigerator while the director’s tragic muse, Edie Sedgwick, sneezed in the background (an attempt to cover her fudged lines). “It was a horror to watch,” stated Norman Mailer.

The following year Ricard starred in Chelsea Girls, Warhol’s split-screen portmanteau tribute to residents of New York’s Chelsea Hotel. The notorious landmark on West 23rd Street was, in reality, Ricard’s on-off home for more than four decades. In its cloistered confines he wrote poetry and art criticism, painted experimental oils and nurtured his reputation as a recluse. “Don’t call out 'René! René!’” he remonstrated with one visiting interviewer. “I know who I am. You have to knock and say, 'It’s Ariel’ so I know it’s you.”

Rene Ricard and 'Homeland' star Claire Danes with one of his art works, 'What Every Young Sissy Should Know' (ALAN DAVIDSON)

Albert René Ricard (he was always known by his middle name) was born on July 23 1946 in Boston where, as a gay, gangly teenage aesthete, he later modelled for the city’s art schools. In the early 1960s he moved from Massachusetts to New York, quickly settling into life as a struggling poet, before meeting Warhol in 1964 through the artist Al Hansen.

Ricard’s time at The Factory saw him experiment with acting (including the title role in The Andy Warhol Story in 1967, a self-flagellating biopic made by its subject) along with free verse. He would sit at their “happenings” wrapped in furs. “The Factory was a cold, frightening, forbidding place,” recalled Ricard. “I mean, it was all silver. It was frigid. Andy never gave us money but he took us out to eat every night. He’d take the whole Factory to a place called Emilio’s and would be so high on amphetamine that he couldn’t eat. He’d serve himself an olive and cut it into 36 slices with the knife and fork.”

In October 1978 the Chelsea Hotel became synonymous with debauchery when Sid Vicious was arrested in Room 100 for the murder of his girlfriend, Nancy Spungen. In the aftermath, Ricard penned a column for the New York Times justifying a bohemian hotel life fuelled by other people’s money. “I should be paid to go out,” he postured. “You see, I’m good for business. I class up a joint.”

During the 1980s Ricard’s art criticism for Artforum and Paris Review promoted the fledgling talents of Keith Haring and Julian Schnabel. In 1981 he published a piece entitled “The Radiant Child” which introduced the work of Jean Michel-Basquiat, the black graffiti artist who would become the enfant terrible of the Manhattan art scene. Ricard’s interests were unapologetically avant garde, although some journalists claimed he eschewed objective criticism in favour of “high-octane” appreciations built on “panegyric, vituperation and gossip”.

His other art writing included a monograph on the Italian painter Francesco Clemente (a 1999 collaboration with the photographer Luca Babini) and exhibition catalogues for shows by William Rand (Bleeker Gallery, 1989) and Philip Taaffe (Gagosian Gallery, August 1999).

Life at the Chelsea was monastic; his apartment consisted of a single room and a shared bathroom (he ate out). “I don’t own anything,” he said in 2007. “I always manage to come up with the rent, knock wood. 'Poet’ is not a salaried occupation. And anyone reading this who’s in need of a poem, we can talk.” Being a man of letters at the Chelsea was not, however, without its benefits. “He writes something and brings it downstairs,” said his neighbour Raymond Foye. “I type it up, he likes to revise. It’s a very rewarding relationship.”

Ricard published four volumes of poems: René Ricard 1979–1980; God With Revolver (1990), which included his artistic representations of the poems; Trusty Sarcophagus Co (1990); and Love Poems (1999), which collected his verse alongside drawings by Robert Hawkins. His poetry echoed the streetwise wisdom of Leonard Cohen’s songs. In The Death of Johnny Stompanato (named after the gangster killed by the daughter of his lover, Lana Turner) Ricard detailed the aftermath of a punch-drunk romance:

“So you submit to that mild form of boxing called love.

Then, happy he’s earned his keep.

He picks your pocket, drives off in your blonde Lincoln

And you pass out.”

A 2003 show of paintings and drawings in New York was followed, in 2008, by an exhibition of new work at London’s Scream Gallery, staged by Julian Schnabel. “He was this invisible force behind so many artists in the Eighties,” said Schnabel of Ricard, adding: “There’s a lifetime behind his work. He’s a grown-up.” In his late work he scrawled neon shades of green, orange and blue text over his and others’ oil paintings. One canvas has the adage “Sometimes it’s OK to throw rocks at girls” scribbled over a painting of a diamond ring. Collectors of his works include the model Kate Moss and the music producer Mark Ronson.

Ricard’s eclectic artistic trajectory was, he maintained, all intended “to amuse and delight, giving my rich friends a feeling of largesse, my poor friends a sense of the high life and myself a true sense of accomplishment for having become a fixture and a rarity in this shark-infested metropolis.”